The Freedom of Flexibility

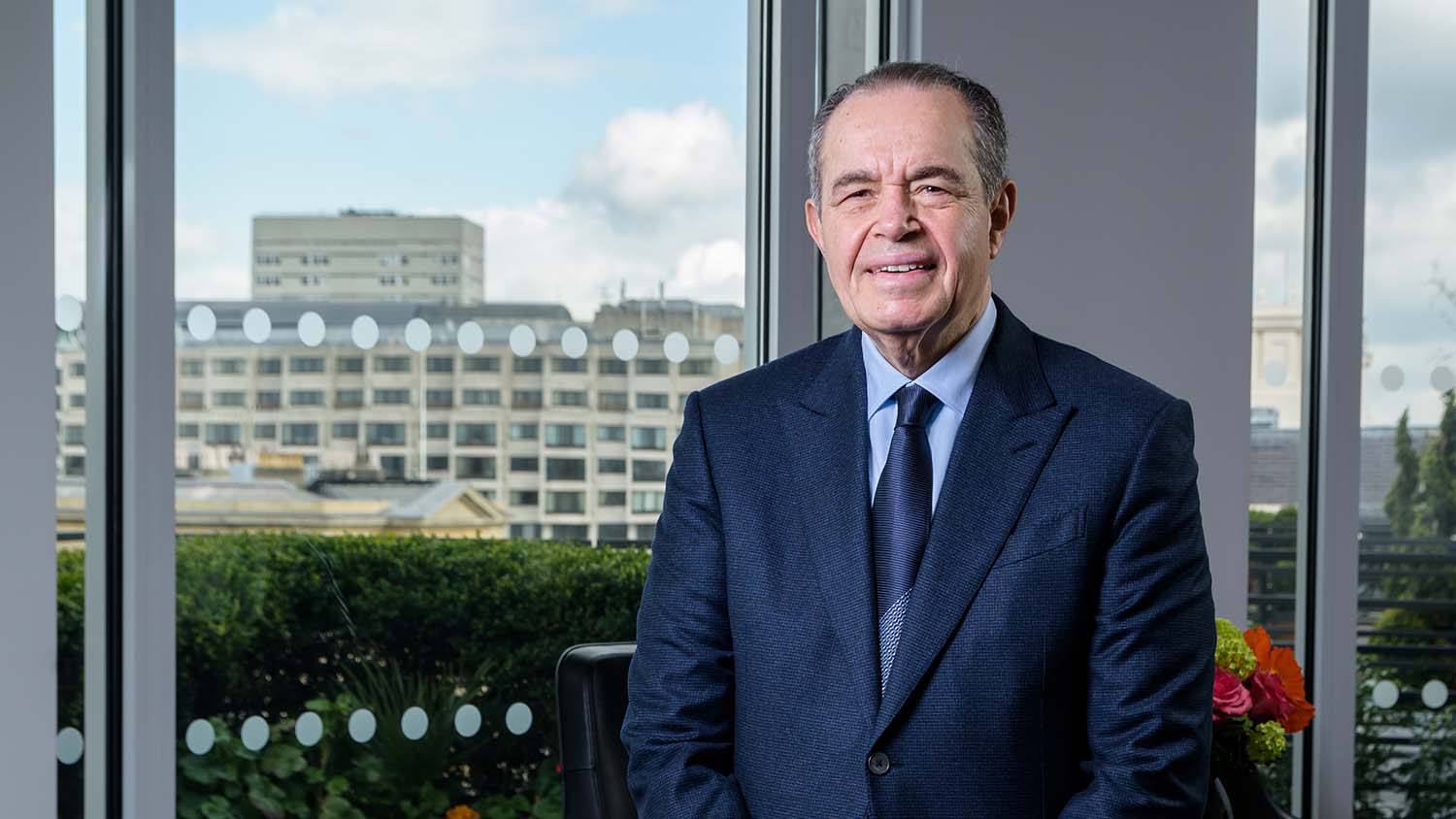

Sometime between 2003 and today, Dr. Thomas Schaefer looked around and realized he was one of the more senior faculty members in NC State’s Department of Physics. His office is a testament to that fact.

Books are piled high on Schaefer’s desk and in a bookshelf in one corner. His door proudly displays posters from physics symposiums of years past. Perhaps most telling, though, is the well-used large chalkboard hanging behind his chair, still full of diagrams and equations. It seems to be just the right thing to pull the whole scene together. A dry-erase board would stick out like a sore thumb.

Schaefer dedicates his research time at the university to studying quantum chromodynamics. That means that he researches how particles behave under circumstances that mimic the early universe. This involves studying matter under many extremes: as hot as T>10¹⁰ Kelvin or as dense as 10^¹⁴ grams/cm³.

So just that little bit of extra money [from private funding] is super useful. I think if we can offer that to somebody who comes in, I think it is attractive.

In 2018, Schaefer was named the Wesley O. Doggett Distinguished Professor for the Department of Physics. This distinguished professorship was created through private funding by alumni of the department, many of whom were taught by Wes Doggett himself.

Doggett was one of the first graduates of the university’s Bachelor of Nuclear Engineering program and was a member of the physics faculty for 35 years, retiring in 1993. A dedicated academic, Doggett encouraged generations of students to pursue graduate degrees and research in the field. He passed away in 2013.

When he first heard about being named a distinguished professor, Schaefer was overjoyed. And while he doesn’t recall meeting Wes Doggett himself, he feels a sense of honor to hold this position because of how Doggett’s students — the main donors that created the professorship — spoke so highly of him.

“He clearly had a large impact on his students,” Schaefer said. “[The donors] had many stories about their time as students here. That’s in some ways why they wanted to give back to the department. They really felt that he had been very influential for their development, not just as physicists or scientists, but as people.”

One might imagine that someone as experienced as Schaefer would have the luxury of seeking whatever knowledge he desires to expand the field of physics through compelling research — however, the reality can be more nuanced.

Instead of enjoying free reign to theorize as he sees fit, Schaefer is often limited in his work by funding granted to him by the Department of Energy. This federal source of funding is finite and comes with many strings attached. Over the years, the rigidity of these grants has tightened significantly. Researchers like Schaefer are limited in the size and scope of their projects and are often forced to pursue avenues that have clear outcomes instead of those that may push the envelope of creativity.

“[Most of the federal funding] is for a very specific project, and we have to write reports about it and we have to announce what it is that we’re going to do,” Schaefer said. “And then three years later we have to announce that we actually did do it and so on. So we can’t just say ‘Oh, I realized that there was actually something more interesting to do and I did that instead.’ [The Department of Energy] is a big institution and they move slowly and that’s just not how it works.”

Upon being named a distinguished professor, however, Schaefer was suddenly afforded a pocket of annual funding to be used as he prioritized. This flexibility quickly became valuable across a number of dimensions.

For many innovators in the U.S., research opportunities can carry a hefty price tag. It costs money to get the needed equipment to try new ideas, pay graduate students and postdoctoral scholars, and frankly, deliver results.

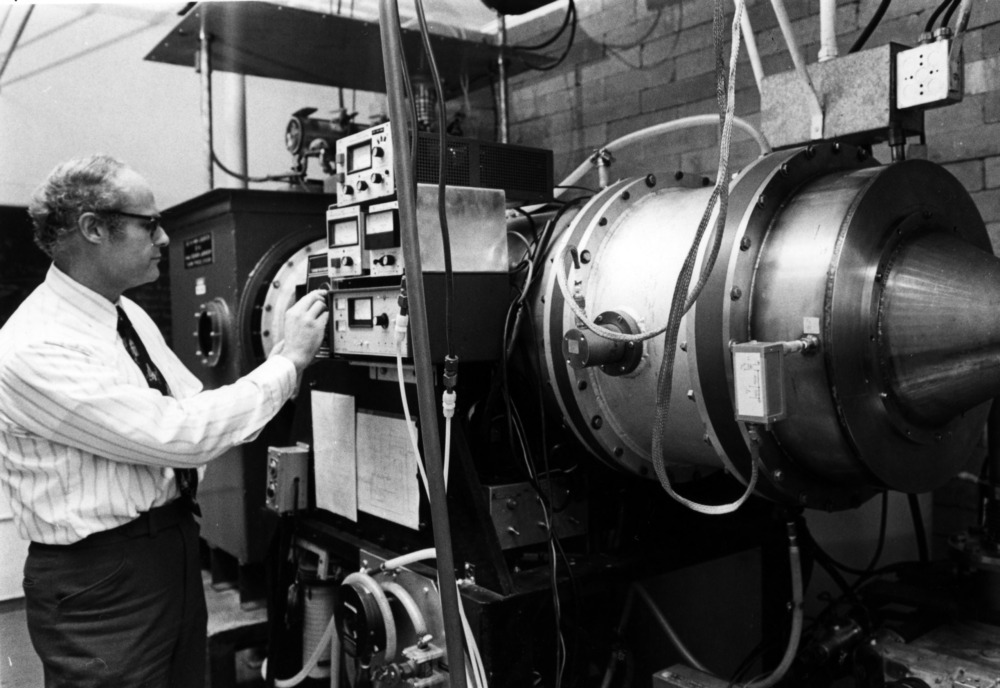

For example, the primary work that Schaefer specializes in includes examining the results of collider laboratories across the United States and Europe, one in particular being the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) on Long Island in New York. The machine takes relativistic heavy ions with large nuclei, accelerates them to very high energy and collides them together. The goal with the nuclei is to create as much energy density, heat and pressure as possible in order to “re-create” the conditions in the early universe. Schaefer can then study the experiments and analyze theories from the results.

One aspect of those experiments gave rise to a number of complex equations that needed to be computed in order to test a new theory. Schaefer thought he could just solve the equations on his laptop but quickly realized that wouldn’t work.

The solution? Purchase what is essentially a “supercomputer” online and enlist a talented undergraduate to complete the computations on the machine.

The Doggett Distinguished Professorship funds helped purchase the equipment and gave Schaefer the ability to pay the student for their time as well. With the complications of the whole process, he said that requesting federal funds for this effort would have been nearly impossible.

When you do not need to pursue a project just to show a result, he explained, you are awarded the creative license to forge new paths. You can go after newer concepts in your field or you can aim to identify new phenomena completely.

“So if you just have something that you want to try and you’re not sure whether this is going to go anywhere, [the professorship endowment] has just a little bit of money and you don’t have to write an application for it or write a report; this is incredibly useful,” he said. “Someone gives you a lot of freedom to explore new things even if you don’t know if it’s going to work out.”

Another area that Schaefer regularly turns to is using the professorship funding to hire and retain graduate students to assist in research. He prefers to take on just one or two students each year in order to closely follow their projects and offer guidance and expertise.

The Department of Energy funding is normally enough for him to pay his students for part-time research throughout an academic year. They can also get paid to teach part-time and get experience in both aspects.

The annual federal funding tends to run out during the summer, though, which is also the time most graduate students should be devoting full-time to their research. If not, graduation timelines can be stretched.

“The time it takes students to graduate has slowly drifted up over the years, and that is something that we really, really wish to avoid,” Schaefer said. “We don’t want to have graduate students spend five, six, seven years to graduate. It’s not good on many levels. At least we want to make sure it’s not [due to a lack of] money. We can pick them up full-time where they don’t feel like they have to earn some extra money and it slows them down even further or they have to take out loans. We really, really want to avoid that.”

Finally, Schaefer recognizes distinguished professorships like his have the potential to attract top university academic talent to NC State and retain them. The afforded flexibility and license for creativity can be a powerful force in faculty choosing between universities.

“If there’s something you really want to do — you’d like to have a small meeting with colleagues, you’d like to start a new research project and you need just a little bit of computing — that kind of flexibility, it’s really hard to get,” Schaefer said. “So just that little bit of extra money is super useful. I think if we can offer that to somebody who comes in, I think it is attractive.”

The flexibility certainly has been for Schaefer. And beyond that, this professorship — and its namesake — has inspired him to think about what legacy he would like to leave behind himself.

“It means something to me and it’s a responsibility that you would like to have the same impact on your students,” he said.

- Categories: