Ring Those Bells: A Carillon Q&A

Learn more about playing carillons from the first person to perform on the one in NC State's Memorial Belltower, carillonneur Tom Gurin.

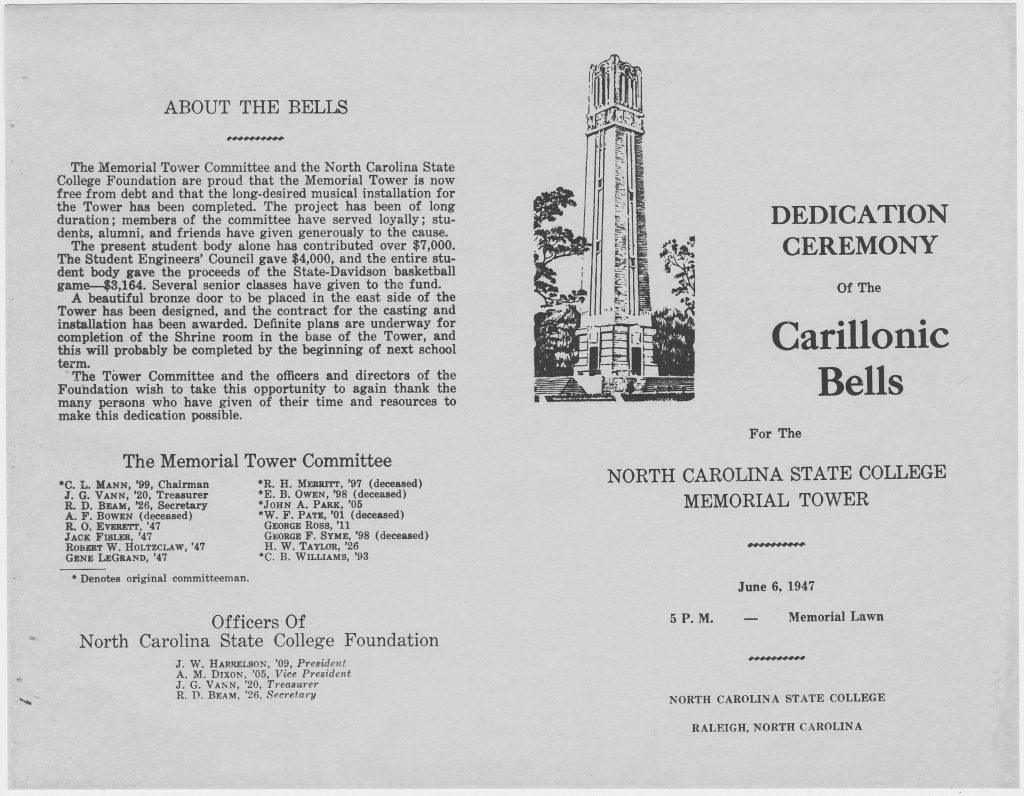

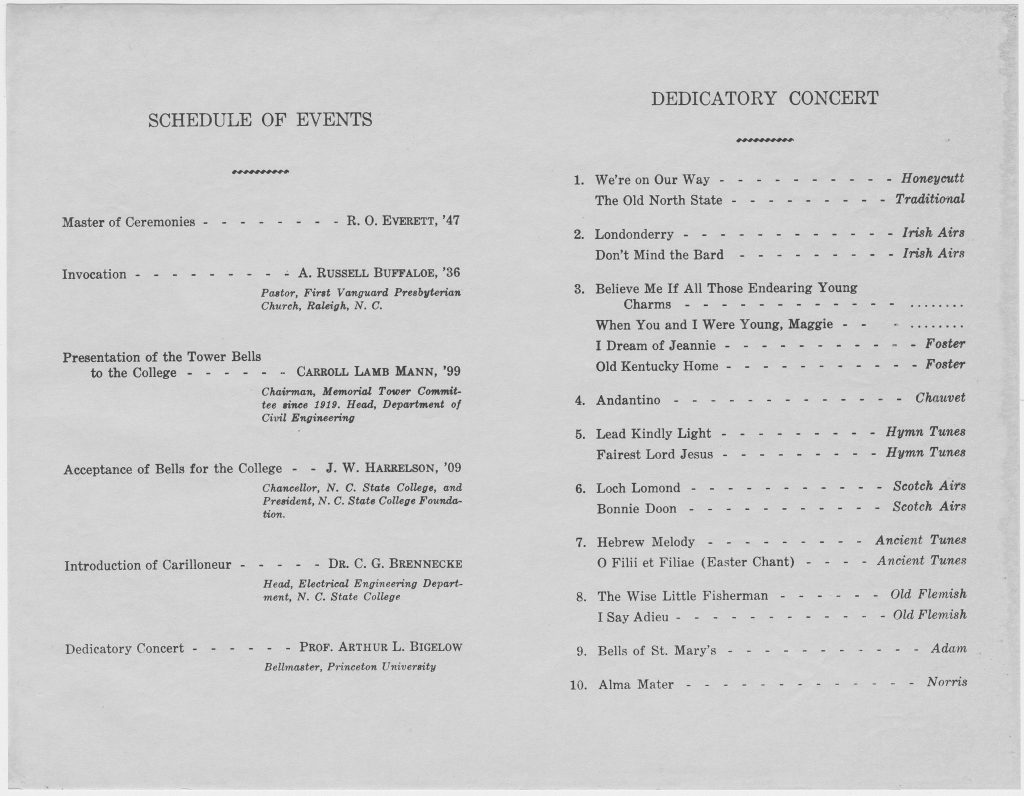

This story is part of an ongoing series highlighting the restoration and completion of the Memorial Belltower. Click the link to learn more about the history of NC State’s Legend in Stone.

On May 14, carillonneur Tom Gurin donned a coat and tie and climbed about 124 stairs to the new playing cabin at clock level in NC State’s Memorial Belltower.

As the university reopened the tower after a lengthy construction and restoration project, and dedicated its surrounding area as Henry Square, we also debuted our new 55-bell carillon.

Gurin’s inaugural performance on that instrument included classical and popular selections, as well as a few pieces that reflected the tower’s history and even a couple requested by donors to the transformational Belltower project.

A graduate of Yale University, Gurin earned a degree in music with distinction and was president of the student-led Yale University Guild of Carillonneurs. He holds an artist diploma with great distinction from the Royal Carillon School in Mechelen, Belgium. Gurin currently serves as Duke University Chapel carillonneur and has been a carillonneur in residence at Holy Name of Jesus Cathedral near NC State’s campus.

As he welcomed NC State’s carillon to the Triangle, we had the opportunity to ask him some questions about his musical art.

What does it mean to you to be performing the inaugural concert for the Memorial Belltower at Henry Square?

I am honored and humbled to be performing the inaugural concert at Henry Square. Playing this role in the history of the Belltower is a privilege. The Memorial Belltower represents so many traditions within the NC State community; it is truly the symbol of the Wolfpack. This concert, which is a century in the making, should be heard as the Pack’s loudest “howl” ever and the beginning of a new tradition on campus.

Why and how did you become a carillonneur?

Carillons are compelling. The bells themselves are rich with colorful overtones as well as complex symbolic meanings and associations. Some people associate bells with war, while others hear them as voices of peace. These nuances add extra dimensions to carillon music.

I began playing the carillon during my first year at Yale University after studying classical clarinet performance and jazz drumming throughout high school. Yale’s carillon attracted me because, just as it is at NC State, the belltower there is the icon of the school. In addition to being a war memorial, the carillon represents the booming voice of the student community. In fact, about 50 people signed up to audition for the Yale Guild of Carillonneurs (a group made entirely of students).

Following 10 weeks of lessons, I was one of the lucky six who were tapped for the job that year. (The following year, when I was teaching my own students, 100 people signed up to audition.) After graduating with a degree in music, I received a fellowship from the Belgian American Educational Foundation to study carillon performance and composition at the Royal Carillon School in Mechelen, Belgium. I received my artist diploma there with great distinction in 2019. I have performed on about 100 carillons around the world.

For the completely uninitiated, what is a carillon in the simplest terms, and just how different and similar is it to a piano or organ?

I am guilty of using the phrase “kind of like an organ but with bells” in my usual 30-second elevator pitch about the carillon. However, they are really apples and oranges.

Although carillons have two keyboards (one for the hands and one for the feet), the playing technique is very different from those of other keyboard instruments. Pianists and organists play mostly with their fingers, whereas carillon keys are spaced much farther apart so that they can be struck with closed fists. This is because most of the keys are too heavy to press down with a single finger at fast speeds. Unlike most modern organs, which are electrically powered, carillons are entirely mechanical and offer no assistance aside from springs and levers. Because they are human-powered, playing the bigger bells requires a lot of force. For this reason, it is tricky to play across the upper and lower registers of the carillon quickly while maintaining acoustic balance and bringing out melodies.

Another difference is that carillonneurs cannot control “sustain” in the same way that other keyboardists can. If a pianist or organist holds down a key and then lifts up their finger, the note should stop. However, it is impossible to dampen a massive bell; once I strike a note, it will last as long as it takes to naturally dissipate. For the larger bells, that could be minutes, depending on how hard I hit it in the first place. This is of particular importance to composers of carillon music.

Finally, carillonneurs are typically hundreds of feet off of the ground during a performance. We are so far away that we hear the music differently from the audience. By the time the sound waves travel to reach other listeners, they will have blended together and been filtered by the air or wind. In Belgium, my teacher would sometimes listen to me playing from a quarter mile away and then call me on my cell phone to communicate his feedback. Carillonneurs must be able to “predict” how the music will sound on the ground based on factors such as tower’s height and design (i.e., whether it is “open” or “closed” at the top), the architecture of nearby buildings (sound can bounce off walls) and even the weather.

Although I often describe carillons as “kind of like an organ,” the experiences of playing on, composing for and listening to a carillon are entirely unique.

How far does the sound from a carillon like ours travel? When you rehearse, is it possible to “turn down the volume” or can everyone always hear you? Do you also rehearse on a practice carillon that’s more secluded?

The carillon has one of the largest dynamic ranges of any musical instrument. Depending on the size and proximity to traffic, the sound of some carillons can carry up to a mile away. I am unsure how far away the NC State carillon can be heard (anyone want to help me with a little experiment?), but I’m guessing the sweet spot is at about 100 yards away, in the direction away from the traffic.

Played with a lighter touch, carillons can sound extremely quiet. Playing quietly is often more difficult than playing loudly. Capable performers will utilize the entire dynamic range of the instrument for musical expression. However, because it is impractical to practice all of my music at ppp (that’s very, very quietly), it is necessary to use a practice keyboard. These instruments replicate the setup of a carillon keyboard but, instead of being attached to bells, they are attached to something quieter like a xylophone. It is absolutely essential for a carillonneur to have access to a practice keyboard. I use the practice keyboard at Duke University for several hours every week.

Our carillon has 55 bells. What does that mean in terms of octaves and comparison to others you’ve played? Is every carillon (and even the way its notes are numbered) a bit unique?

Fifty-five bells make about four and a half octaves. That is a wider range than most carillonneurs enjoy (two octaves is the minimum; four is standard). Just about every single carillon is unique, yes. For example, the largest bell at NC State weighs some 1,800 pounds. At Duke University, the carillon has only 50 bells. However, the largest weighs more than 11,000 pounds. It’s kind of like playing a violin versus an upright bass. The NC State carillon is especially unique, however, because of its beautiful sound. I spend a lot of time listening to bells and carillons (a LOT of time) and B.A. Sunderlin, the bellfoundry that cast and tuned NC State’s carillon, created an instrument that is very aurally appealing. It’s basically a Stradivarius.

Playing a carillon is a bit of a workout, correct? Even just climbing the stairs to most of them, not to mention that playing seems to be a very manual process? Do carillonneurs end up with blisters, calluses or other playing-related ailments?

Yes, yes and yes. It’s amazing what we do for the love of music.

Can one play just about any kind of music on a carillon? What is your favorite kind of music to play, and what’s most challenging?

The short answer is yes, for the most part. Rap and hip-hop music are challenging to play well on the carillon. I enjoy playing film music (“Moon River,” “The Godfather,” “Star Wars,” etc.). I like to play Disney songs, pop songs or other tunes that are somewhat recognizable. My hope is that someone who is on their way to class or who might be having a bad day will stop and smile. I play a lot of Bach, too.

I also like to do holiday-themed concerts. Valentine’s Day (“Single Ladies”) and Halloween (“Toccata in D Minor”) are always favorites.

At the same time, I am constantly working on new compositions to play on the carillon. One of my original compositions was published in 2019, and another will be published this summer. There is a wealth of music composed specifically for the carillon, including works by Samuel Barber, George Crumb and Nino Rota. Surprisingly, carillons don’t have to be solo instruments. I have composed and performed pieces for carillon and choir, carillon and flute, and more!

Carillonneurs seem to be a relatively small but very passionate group. Do you all travel around to play everywhere possible?

I have been a member of the Guild of Carillonneurs in North America since passing the exam in 2017. This group gives carillonneurs (who, by nature of the job, are usually isolated) a forum to convene and exchange ideas. It is common for universities and churches with carillons to host a series of evening recitals each summer, often in July or August. These are excellent opportunities for audiences to enjoy different styles of playing and for carillonneurs to hear their own instruments from the ground. For example, I will be performing several guest recitals this summer, including concerts at the University of Michigan and the University of Rochester.

What can an instrument like this one mean for NC State? Any chance of some friendly competition with the Duke folks?

It all depends on how we use it. There is an opportunity here to become a hotspot for carillon studies like at the University of Michigan, University of California-Berkeley and others. Will a carillonneur perform daily or weekly recitals? Will students have the opportunity to learn to play the instrument themselves? I’m all for some friendly competition!

What is your favorite thing about playing a carillon?

My favorite thing is to bring small groups of people upstairs to show them how the instrument actually works. There is often an aura of mystery surrounding carillon towers, since it is impossible to see the action during recitals without a live video feed. Because I can’t bring the keyboard downstairs, it’s sometimes fun to bring the audience up for a visit.

Have you had any interesting animal encounters up in belfries?

Sadly, most of my animal encounters in belfries have been with wasps.

Is there a misconception about playing the carillon that you commonly encounter when talking to the regular folks about your work?

A common question I get is, “How do you pull all of those ropes at the same time?” The bells in a carillon do not move. As much as I enjoy pulling ropes and talking to statues, I am no Quasimodo. Swinging bells, change ringing and carillons are all distinct forms of bell-playing with different histories. There are many, many ways to play bells, and I have tried a handful of them. Carillon performance, which does not involve any ropes, happens to be my personal favorite.

- Categories: