Breeding a Berry Successful Career

When you buy strawberries in the grocery store, what you taste is the top 1% of the product.

Gina Fernandez tastes the rest.

What is she looking for? “Flavors, sugars, texture — it’s a lot of different traits that make a berry taste good, and I evaluate hundreds of berries each year for those traits,” she said.

She and her team have started screening breeding material for a couple of genetic markers to make the job easier. One genetic marker indicates more of a grape flavor, for instance, while another yields a peachier taste. They will be able to eliminate plants that don’t have those flavors before tasting begins.

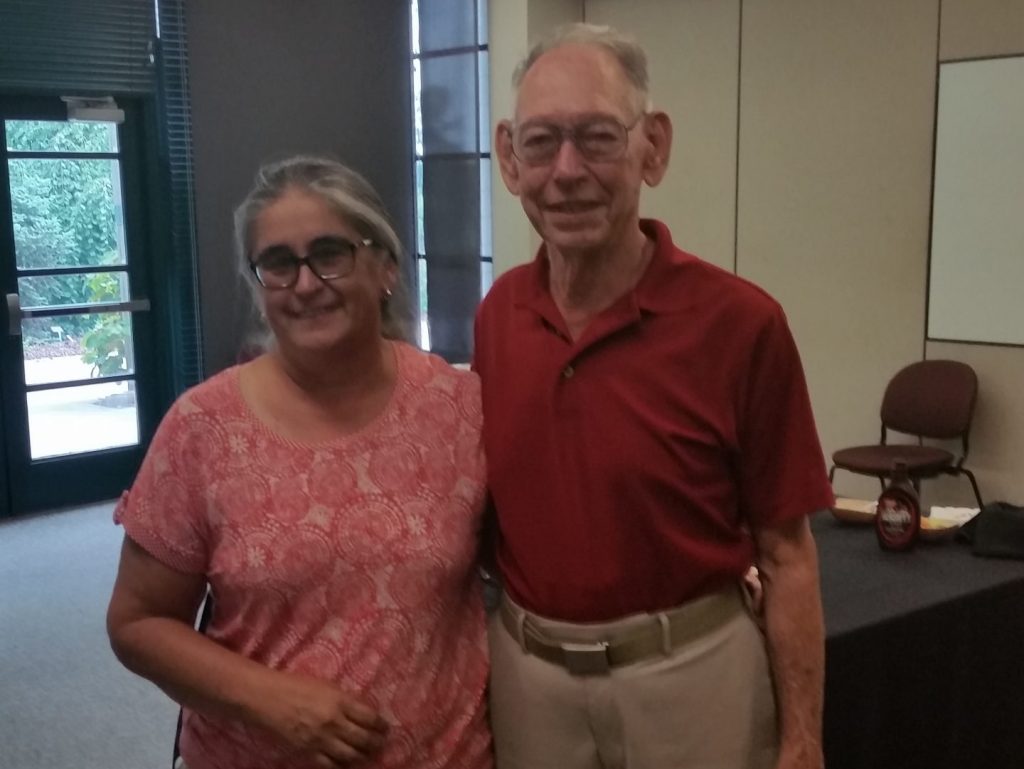

Fernandez, NC State’s John D. and Nell R. Leazar Distinguished Professor of Horticultural Science, brought her small fruit expertise to the university in 1996. She and her husband, Craig Yencho, had decided to move wherever one of them was offered a job first, and they had been about to leave for a research station in Colombia when NC State called with positions for them both.

“The blackberry industry in North Carolina was at its infancy and ready to grow, and it was perfect timing for me to come here. It worked out really well for the two of us,” Fernandez said.

It has also worked out well for growers. Fernandez is the state’s strawberry, blackberry and raspberry breeder, carrying out research at four stations from the mountains to the beach. North Carolina’s varied climates across these regions allow her team to pace the harvest season.

Hired as an assistant professor and extension specialist, Fernandez was named a full professor in 2010 and the Leazar Distinguished Professor of Horticulture Science — a position that was created during the Think and Do the Extraordinary Campaign — in 2019.

“It’s recognition of the work that I’ve done, and it’s really nice to have that opportunity to be recognized beyond the full professor title,” she said.

As part of her NC State Extension responsibilities, she has developed a pest management strategic plan and crop profile for Southern blackberry growers, which will be used by the EPA and USDA. She also helps growers identify damage after freezes and develop fertility plans for fall and summer fruiting berries.

It’s a non-traditional split to work in both breeding and extension, but it aligns well for Fernandez because, as she puts it, “Growers like new varieties.”

Fernandez’s current research is focused on developing those new varieties of strawberries, blackberries and raspberries, which she finds fits perfectly within NC State’s think and do motto.

“We get to think about what needs to be done to develop a new strawberry — for example, one that grows early and is disease-resistant and tastes good. And then we do the work. There’s a tangible outcome,” she said.

Working with caneberries — the delicate fruit that grows on the woody stems (or canes) of plants in the genus Rubus — has long been a passion of Fernandez’s. Her Ph.D. dissertation focused on the heat tolerance of raspberries. (It’s low, which is why it’s challenging to grow raspberries in North Carolina, though she continues to work to change that.)

“Caneberries are cool. I just love the fruit,” she said. “I love the growth habit. They have this biennial growth habit, where they have a first year cane and a second year cane, and you can manipulate it to fruit at different times. It’s a unique growing system.”

Examples of fruit Fernandez’s team has developed include the ‘Von’ blackberry, which is a berry that ripens late in the season with good yields that meets the needs for growers in Western North Carolina. The ‘Nantahala’ raspberry — which in 2009 was the first red raspberry released from NC State’s breeding program in 50 years — also grows well in the cooler weather of the mountains, though for an NC grower, it couldn’t compete commercially against California’s berries.

However, the ‘Nantahala’ raspberry found a second life with home growers. Commercial nurseries like Gurney’s have helped the plant find its niche, and it sells out every year. “And especially now with COVID-19, people want to grow things in their backyard, so I think it’s going to be even more popular,” Fernandez said.

This career is one she never anticipated as a college student interested in science. She knew she liked plants, and she liked being outside, but growing up in rural Wisconsin, her main association with agriculture was dairy farming. Exploring various plant-related options as a master’s student, she shadowed a professor collecting data in an apple orchard.

That experience opened up a whole new world — one that balanced agriculture and horticulture with lab research and field work.

“It was a beautiful day to be conducting research in the orchard— the sun was out, the birds were singing. I thought, sign me up! This is great,” Fernandez said.

She once shared that story while speaking to students on a panel with Bryce Lane, retired NC State professor and former host of UNC-TV’s ‘”In the Garden with Bryce Lane.”

“I told the students, ‘I don’t know how I got here, but I can tell you that there are things that happened that put me on this path. Bryce said it was exactly what students need — to listen to the little nudges you get along the way,” she said. “I feel very, very lucky to have landed here at NC State.”

Now, as a distinguished professor, Fernandez is in a position to bring her skills and knowledge full circle, providing those same nudges to students by hiring them for undergraduate research positions. Resources from the Leazer professorship make it possible to give them hands-on experience with plant breeding, such as making crosses — transferring pollen from the male plant anther and applying it to the female stigma.

She has also been able to hire an undergraduate student to assist with important projects that wouldn’t necessarily be fundable by grants, like preserving core germplasm from different strawberry varieties in tissue cultures. The germplasm is the collection of genetically distinct plants Fernandez has used to breed from, for example using plants with traits like for disease-resistance and crossing them with plants that have large fruit. The project creates a library of sorts, which allows Fernandez to preserve different berry genetics for breeding projects at any time, without having to worry about losing valuable plants in the field.

Being able to offer these experiences — as well as show what’s possible in this career field as a distinguished professor — is particularly important to Fernandez as a woman of Hispanic descent in academia who was a first-generation college and graduate student. While she hasn’t set out specifically to mentor women students, she finds that many do come work with her.

“It’s fun to give them these opportunities and show them that they can do these things too,” Fernandez said.

While not all of her students will become plant breeders, they enjoy their time with the program and being part of a collaborative group — Team Rubus, as they call themselves.

The team will continue their work throughout the spring and summer as they test and taste. And though they might have their fill of that bottom percentage of fruit by the end of the season, Fernandez and her students will be ready to experience the diversity of North Carolina berries again next spring.

Fuel Our Growth

- Categories: